Art in the Uncanny Valley

A new exhibit at the National Museum of Women in the Arts touches on all kinds of the weird and wonderful.

I don’t know if you remember the Garbage Pail Kids – I promise this is eventually going to be about the new Uncanny exhibit at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, so stick with me. The Garbage Pail Kids were a line of miserable little cards all featuring horrific depictions of weirdo kids. Things like Up Chuck and Crater Chris and Adam Bomb decorated with the most revolting pictures. Designed to make little kids laugh and eww and to make parents say, “No way in hell.”

The really gross parts of the cards are all takes on real things – rotting teeth, scabs, brains, etc. – all blown up and slightly twisted in their presentation. As a kid, it was one of the first times I remember feeling like an image was wrong. Not morally wrong, but like there was something the picture was doing that evoked a really primal, guttural response in me.

That link between the real thing and the twisted version of the thing is what Freud – a man I’m generally fine to take or leave – is getting at when he talks about the uncanny. Uncanny things are the ones that reveal the bits of reality we know are there, but willfully or unconsciously hide. They’re scary or grotesque because they’re so easy to connect to what’s real.

I’m sure that’s – let’s guess – 83% off-base, but I’m not a Freud guy and we’re still in the introduction here, so we’ll gloss over all the details.

The idea of the “uncanny valley” gained popularity in the early 2000s as a term for the way we perceive technologically created versions of humans. At the one end, you’ve got Elmer Fudd, who’s so clearly a representation of a person that no one could possibly confuse him with an actual person. On the other end, photorealistic paintings of eyeballs that make you stare and wonder how they’re not actually photographs.

Then, about two-thirds of the way between those ends, there are the CGI people in The Polar Express movie. They look really close to real, but not quite real enough to trick you. Instead, you notice all the ways they’re simultaneously like and unlike humans. They don’t move right. They blink weirdly. They’re all proportioned about right, but maybe the fingers are slightly wrong or the ears stick out at an unnatural angle.

Shudder.

The current exhibition at the National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA) is called Uncanny, and you’ll never guess what it’s about – that’s right, K-pop. No, it’s a series of pieces that highlight the uncanny nature of representation. Odd photographic angles and almost life-like wax figures and headless bodies made of burlap.

It’s an exhibit designed to poke at all the little queasy feeling art can bring up. You walk in faced with the burlap people all sitting stoically in front of you. An eyeless gallery of observers watching you in the front room. Probably judging me for not spending long enough in front of the one piece and too long in front of the other.

That was a thing I used to really worry about, by the way. I’d walk around in museums and imagine other people around me noticing how long I stood in front of the painting they really liked. Thirty seconds, huh? Took that Monet in pretty quickly. I guess you noticed all the overpainting and subtle lighting – you must be very good at this.

Now I’m better at treating museums like concerts. Sure, the guy behind me might notice my awkward standing and swaying, but they probably don’t and that’s great because I have a hard time listening to the music while thinking about if my hands have been in my pockets too long – another old worry of mine.

Opposite the watchers – that piece is actually called 4 Seated Figures and it’s by Magdalena Abakanowicz – there are two pieces from Remedios Varo, a surrealist painter working in the mid-1900s. They’re kind of like Dali pieces, which everyone says, but without the middle school kid vibes. I’m not a huge Dali fan – you may not have guessed – but the Varo paintings are wonderful.

The exhibition sprawls out from there. One of the interesting parts of this exhibit space is its slight warrenness. It’s not a clean loop around the building, and you’ll end up back in some dead end rooms before you come back along the other side of it. That works with this exhibit because it’s all meant to feel a little confusing and foreign.

There are wax figures with speakers wired into them in one room, like an odd little Madame Tussauds featuring characters from fiction. A few portraits on broken glass, with visages peering out through cracks and gaps. A whole taxidermied taxidermy display case, where the thing that’s being skinned and preserved is entirely man made instead of being a bobcat fighting a – I dunno – rabid squirrel.

Other major standouts include a series from Connie Imboden, a photographer from Texas whose works often include twisted and reflected images. Things that look painful or unnatural, but which are actually just warped perspectives of the world. The picture below – Untitled – took me just shy of forever to process. At first, I thought it was some kind of digital composite. Then I thought maybe all the editing was done in the darkroom. It was only much later that I realized it was a body half submerged in water, reflected on the underside of the water’s surface.

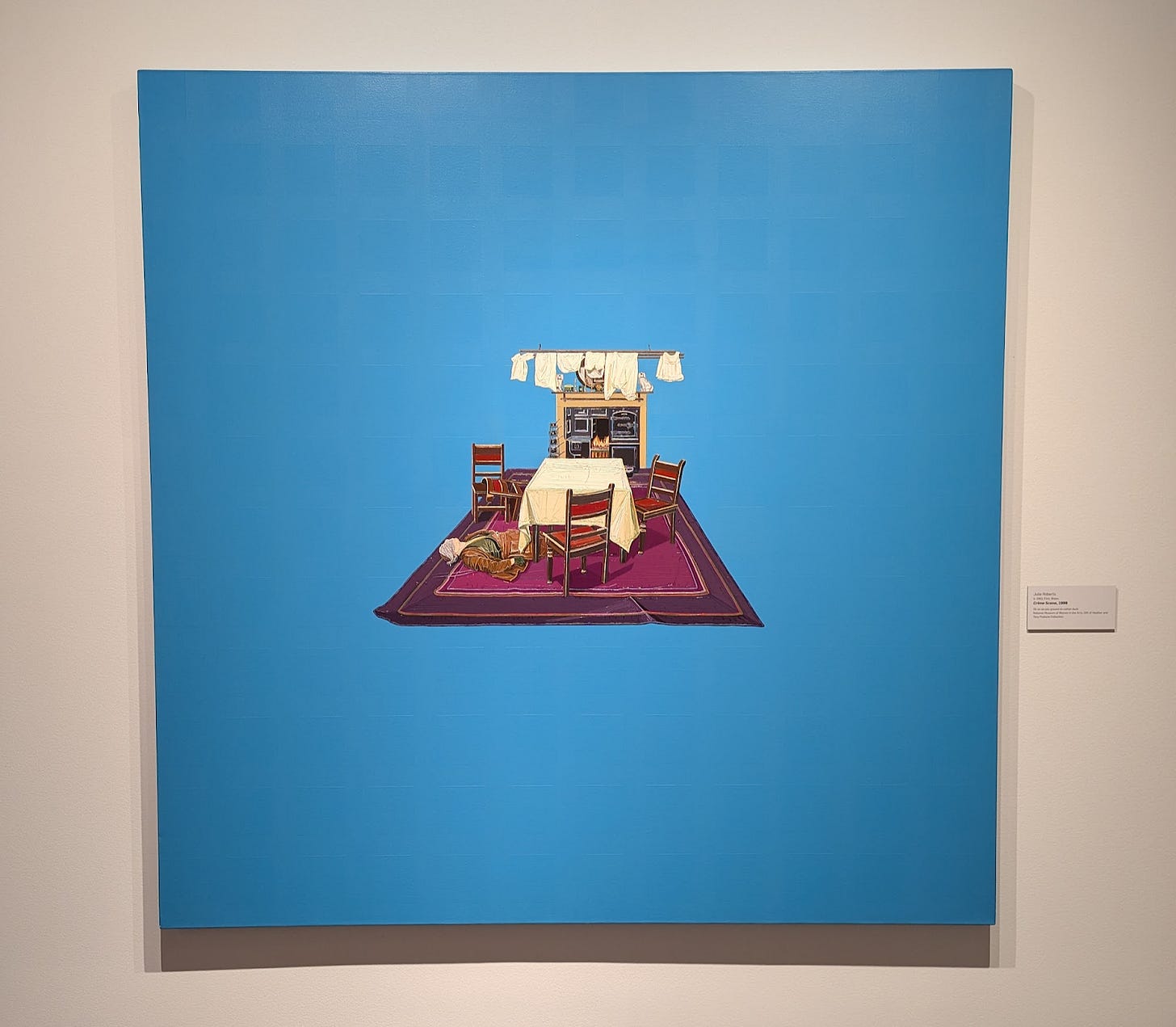

There’s also a series from Julie Roberts, who I hadn’t come across before. She paints these magnificent little scenes on massive canvases. The whole thing is covered in rich color with the scene set in the middle and they look like cousins to Wes Anderson movie sets. These were in one of the last rooms I saw – walking clockwise through the exhibit – and, like a little spoonful of grapefruit ice cream after a big meal, were a welcome splash of color and levity.

They’re not actually all that light in subject, but the immediate sensation is warm and welcoming. Which grapefruit ice cream kind of isn’t, so I guess that’s not a great comparison – we’ll all find a way to get by.

I also want to highlight a selection of works by Gillian Wearing who – and I’m assuming this is a coincidence – makes portraits of herself wearing intricate masks that change her face. She got self portraits of her sister, Meret Oppenheim and Mona Lisa, and each one is a complete mind-twist. You know it’s the same woman behind the mask, but lord knows I couldn’t get my brain to recognize it.

Uncanny is a total win and I recommend it wholeheartedly. The NMWA is quickly becoming one of my favorite places to visit and just exist in. The building is lovely, the selection of art on display is excellent and it’s often quiet and contemplative – a welcome contrast to the NGA as tourist season looms.

Give it a shot and don’t worry about standing around with your hands in your pockets, I promise no one cares.

An addendum

I got two great questions in the comments, both of which a better version of me would have addressed ahead of time.

“1) would you bring a kid to see it? 2) how does the exhibit discuss women and women’s bodies as sources of/in conversation with the Uncanny? like, why is this exhibit happening (in the way it is, or at all) at the NMWA and not someplace else?”

As far as kids, yeah, I’d take a kid to it. Uncanny is – intentionally sometimes and sometimes not – visually joyful and interesting. There are a handful of pieces that I found deeply unsettling, but only because I’ve got a handful of decades of life to draw on. They’re intense because they are uncanny representations of familiar feelings and fears.

If you’re six or ten or fifteen, most of the darkness is likely buried behind the facade. There are a small number of pieces that are going to be a bit intense and there are a few nudes, but the nudes aren’t sexualized and the intense pieces are all metaphorical or interpretive, so I don’t think they would upset.

The upside is huge. There are sculptures to see, the wax people are fascinating to try and understand, Wearing’s pieces are neat to try and unpick and there are all sorts of images that appeal to the kind of kid that would get lost in a Guinness Book or National Geographic. Y’all know your own kids, so take a peek before you drag them through, but I would take mine. It seems like an exhibition that generates an interest in and joy for Art.

Women. Yep, this is at the NMWA for a reason. The curators probably didn’t just think, “I bet this’ll be fun and you can bring kids!”

Uncanny’s focus on the terror and foreignness of the known is meant to parallel the fears, experiences and worries of women. From the feeling of being othered by social norms or consumerism to the lack of bodily autonomy that comes from a relationship, an assault or even from being an expectant mother, women are often put at odds with the things they’re most familiar with.

What does it mean to see yourself reflected in an unfamiliar way? Going to Wearing’s work again, she presents herself as someone else. She could look in the mirror and not see herself reflected because she was – voluntarily here – hidden behind another face.

Imboden’s photos show twisted and warped visions of women’s bodies. The kind of view a woman might have when her identity or image is shown back to her. The feeling of knowing it’s you, but not in a way you recognize or identify with.

If you’re looking for a fun little afternoon read, check out John-Paul Sartre’s Being and Nothingness. In it, Sartre talks about the way we view ourselves when we’re seen by others. For example, imagine I’m walking down the street, whistling the tune to Beck’s Loser – a thing I just did. As long as I’m alone, it’s just me enjoying the tune and the way whistling works and the way the music reflects the cityscape. As soon as someone sees me, that all changes.

I suddenly see that I’m seen, which makes me think about the way that person is seeing me. I’m no longer floating along as Me. I’m now A Guy Who Whistles While He Walks in that person’s mind. I know that, and it thrusts me into the uncanny feeling of not recognizing myself as reflected in that person’s eyes.

That’s some of the root of what’s on display here. Women as perceived or in expectation cease to be the familiar version of themselves. Instead, they’re objects or means to an end or victims or any number of other things that look a bit like the familiar person they know, but crumpled or altered somehow.

In the words of the NMWA

“The exhibition takes as its starting point recent scholarship by art historian Alexandra M. Kokoli, whose book The Feminist Uncanny in Theory and Art Practice (2016) interrogates the complex relationship between Freudian psychoanalysis and feminism. In Kokoli’s view, the uncanny is an aggressive defamiliarization of long-held preconceptions, and it relates to the unsettling goal of resistance and liberation in feminist artistic practices.

Uncanny features works that destabilize gendered and societal preconceptions, bearing witness to women’s complex experiences and worldviews.”

It accomplishes its goal admirably.

thanks for the write-up, it sounds amazing. 1) would you bring a kid to see it? 2) how does the exhibit discuss women and women’s bodies as sources of/in conversation with the Uncanny? like, why is this exhibit happening (in the way it is, or at all) at the NMWA and not someplace else? thanks, Professor.